Japanese society’s regimented and structured approach to living makes it hard to believe that it once was a breeding ground for dangerous youth subculture. We’re talking about the Bosozoku — a menacing biker gang that wreaked havoc on the streets of Japan for over 3 decades back in the late 90s.

These guys rode on pimped-out Honda CB400Fs running obnoxiously loud straight pipes, tucked-in Shibori handlebars, switchblade headlights, Rocket-cowl fairings, tall Sandan pillion seat rests, and just about every mod that would give most bikers an instant migraine.

To be honest, though, they looked sick, and some were done up quite tastefully. If the American Chopper and the British Cafe Racer had a romantic interlude, the Bosozoku motorcycle style could likely be a result.

What ultimately mattered more was not the bikes. It was the people who rode them — alcohol, angst, and testosterone-fueled teenagers in boilersuits, on a mission to preserve a made-up legacy in the name of tradition. What could go wrong?

Unlike the Midnight Club which lived by the rule of never compromising the safety of others, Bosozoku did quite the opposite.

In this guide, we’ll discuss all things Bosozoku — everything from why they existed, their mission, history, and how they influenced fashion and car culture across the globe. Let’s dive right in.

What Does “Bosozoku” Translate to?

Literal translations from Japanese to English hardly ever make sense, let alone do justice to the original idea. But they provide a good frame of reference. The word Zokusha is an exception as it directly translates to gang car — it’s a commonly used word in Japan.

- Boso: Outrage, force, violence, cruelty

- Zoku: Gang / tribe

The biker gang never called themselves Bosozoku. Back in 1970, riots broke out between various Japanese biker gangs and the police which created a media frenzy. It was the media that coined the term, and it stuck.

Bosozoku could’ve very well been inspired by the gang name Kaminari Zoku (thunder gang). These were the ex-military Kamikaze aviators who originally started the gang. Eventually, they were replaced with younger members who were responsible for some of the first riots.

A Closer Look at the Bosozoku

It’s entirely plausible that the Bosozoku were simply a gang of troublemakers who had nothing better to do, but we’d like to believe that there’s a lot more to it than what meets the eye.

Let’s take a closer look at this subculture, understand how it originated, and whether or not it symbolizes something meaningful.

History: From Suicide Pilots to Teenage Rebels

The Second World War left Japan in ruins. While the industrial and commercial infrastructure was swiftly rebuilt, little was being done to rebuild a stable society.

During that time, groups of returning veterans faced great difficulty in readjusting to normal life after the war. These groups also included Kamikaze pilots, better known as suicide pilots.

For those who don’t know, Kamikaze training involved getting the pilots ready for death; they were taught to disregard their earthly life and concentrate on defeating the enemy with unwavering determination. Physically strenuous and torturous corporal punishment was part of their daily routine.

When these groups returned after the war, it was clear that most of them suffered from PTSD. Reminds us of The Gunner’s Dream from Pink Floyd’s Final Cut.

Their mental instability and failure to reintegrate into society pushed them towards taking up reckless activity. As a coping mechanism, they started re-living the comradeship and danger that was once a normal part of their life.

This was fueled by inspiration from American greaser culture and foreign racing movies like Rebel Without a Cause (1959). Perhaps they took the title a bit too seriously.

They banded together as Kaminari Zoku (thunder gang) and began touring around their communities and cities on weekends. There was a lot of reckless motorcycle riding and gang-type activity involved.

Japanese teenagers started looking up to this lifestyle and found it extremely appealing. They could relate to and wanted to adopt the outlaw lifestyle for various reasons. Which they did, and that’s when the riots happened.

This marked the transition from Kaminari Zoku to Bosozoku — from suicide pilots to teenage rebels. They would ride in large numbers, over 100 bikers would cruise together, running toll booths, resisting arrest, smashing cars, vandalizing property; threatening to beat up motorists and bystanders who got in their way.

Rebels Without a Cause

We live in a society that rewards conformity and punishes rebellion. Sure, the rules exist for a reason, but in the land of the rising sun, they’re blown out of proportion. Anything that conflicts with the ideas of nationalism, proper conduct, and social roles has always been severely discouraged.

That’s probably why oppressed Japanese teenagers developed an affinity toward the outlaw lifestyle which the Bosozoku represented.

There’s a reason why it is said that rebels have a place in society. Without rebellion, there is no change. But it’s hard to understand what the Bosozoku were hoping to achieve. Their actions were confusing.

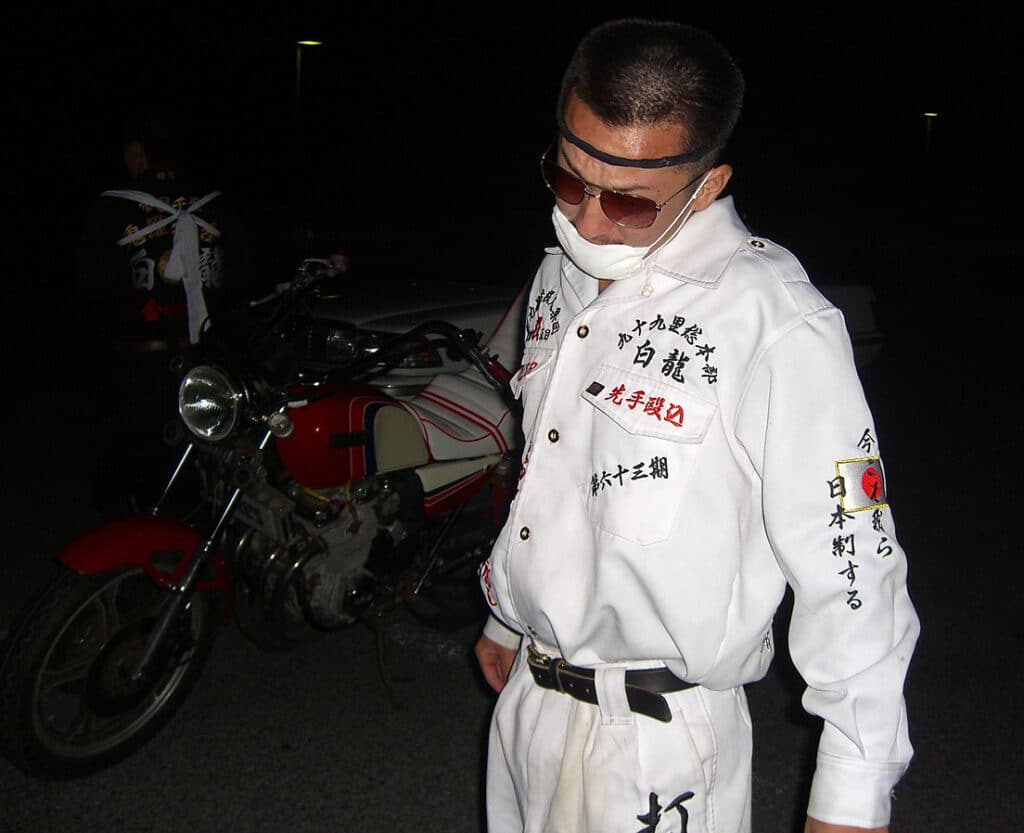

Riding around on outlandish bikes wearing tokkō-fuku overalls, waving kanji slogans that translated to vaguely patriotic and cringe-worthy English catchphrases; displaying far-right imagery such as the Emperor’s Chrysanthemum Seal, rising sun flags, and swastikas didn’t seem to add up.

Most of it was for shock value. A possible reason is they wanted to justify how their gatherings were a form of political expression. They weren’t though.

Maybe the Bosozoku were a symptom of enforcing conformity, Filial piety, and Confucianism which are major parts of the Japanese societal structure.

Maybe it was an Archaic revival of sorts. Or maybe they were just a bunch of buffoons who rode around on de-catted motorcycles, creating a nuisance for a laugh.

True rebels aren’t supposed crazy or out of control. Bosozoku literally translates to “crazy and out of control”. True rebels don’t break the rules because they want to, they do it because they have to in order to improve the current regime.

Whichever way you choose to look at it, there’s no denying that there’s something symbolic about this subculture; whether the participants realize it or not. And the same is true with many gangs and subcultures across the world.

Gang Culture in a Nutshell

Yakuza, Japan’s organized crime syndicate often looked to the Bosozoku for recruitment. That was for a reason — it was a hotbed for crime-ready juveniles looking for a purpose. Ever heard the term “get them young” in the world of recruitment?

The reason why they made the perfect recruits for organized crime was that they were oppressed, belonged to lower socioeconomic backgrounds, were raised in dysfunctional environments, and just didn’t know better. This is commonplace in gang culture.

According to Barrington Moore, Jr., gangsterism is a “form of self-help which victimizes others”. Frederic Thrasher, a sociologist with a Ph.D. in gangs identified “demoralization” as a standard characteristic of gangs.

Every gang packages it differently, but the underlying causes of their behavior are always very similar.

Tupac’s “born black in this white man’s world” refers to seclusion. When people are alienated and secluded from society, they tend to join others who are sailing in the same boat — whether they’re African American outcasts, Sicilian peasants, or oppressed Japanese teenagers.

The only respect the Bosozoku got was from their fellow gang members. They found solace in a subculture that welcomed them.

Bosozoku Fashion

Bosozoku culture as it was back in the day is now gone. Some of it is kept alive today because high-end fashion labels in Tokyo figured out how to sell it. That’s not a bad thing though.

Fashion is a commonly used form of social resistance in Japan, and Bosozoku fashion only scratches the surface on that front. Styles like Harajuku and Yami Kwaii are where it’s at.

The typical Bosozoku style is centered around the ever-popular tokkō-fuku boiler suits, scarfs, gauze masks, Hachimaki, and Hinomaru style headbands — both the traditional and festive types.

The boiler suits were originally worn as an indicator of how unified the gang is. In fashion, they are often left open to reveal sarashi, or bandages wrapped around the torso, paired with extremely baggy pants and jika-tabi boots.

Other accessories include Tasuki sashes, round sunglasses, 50s pompadour hair, and pretty much anything that ties into the Rock n Roll aesthetic. Some of these are so over the top, they’d make Elvis Presley look underdressed.

This style wasn’t limited to attire and motorcycles, it made its way into the car scene and stuck! Bosozoku cars are a sensation — these are even more outlandish than the motorcycles, and they just cannot be ignored.

Concluding Thoughts

So that was our take on all things Bosozoku. What do you think about their actions? Do you see them as a nuisance or as something more?

Would you think twice before sporting a boiler suit and riding around on a Honda CB400F? Let us know by leaving a comment below!

Feature Image: A group of Japanese Bosozoku on modified motorbikes, by SC36, CC BY-SA 3.0